How long do we remember war?

Written by Ulrike Barten, Postdoc. at Department of Law

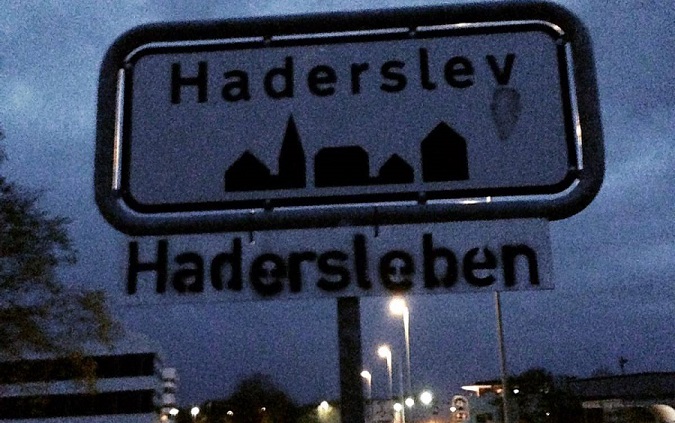

If seventy years later is not the right time to make a symbolic gesture, then when is? In April 2015, the mayor of the Danish town Haderslev put up a bilingual town sign. Underneath the Danish name Haderslev was put the German version Hadersleben in smaller letters. After a few days, the bilingual town sign was taken down in the night by unknown persons. The heated debate in the region shows a majority of those debating being clearly anti-bilingual signs. Among them is a local politician in Tønder, who is uneasy about bilingual signs as he states that we live in a region with a special history where we have undergone Germanification, in Danish fortyskningsproces, so leave this alone and let us be Danes in spirit and soul also on town signs.

Without doubt, World War II left scars in the border region and the German minority holds its share of responsibility, for several thousands of its members collaborated actively and voluntarily with the Nazis. The same did, by the way, “regular” Danes. How much weight does this carry seventy years later?

Photo by "Listeria".

Against bilingual signs

There are two reasons against bilingual signs. Firstly, and this reason by far dominates the discussion, is this sentiment, that the 70th anniversary of the end of World War II is simply not a good time for setting up bilingual signs. The second reason is economic. Setting up bilingual signs in the town of Tønder would cost about 67,000 euro. The municipality’s economic committee voted unanimously against bilingual signs.

In favour of bilingual signs

Are there reasons in favour of bilingual signs? Also here, two kinds of reasons emerge: economics and sentiments. The mayor of Tønder was cautiously positive about bilingual signs as the town has quite a number of German tourists.

The other reason is one of making others feeling welcome. For the German minority, bilingual town signs are about recognition of equal cultures in the border region. It is a matter of feeling welcome with your small differences in the place your family probably has lived in for generations. Thinking about tourists, adding Tondern to the sign could be a warm welcome. To those not familiar with the region’s history it could prompt the question into the unique history of the region. It could actually be a marketing trick.

The larger perspective

The larger perspective offers little against bilingual signs. The Danish and the German minority are not products of World War II but of World War I. They have existed in the border region for ninety-five years.

There has not been a single outbreak of ethnic unrest or violence since the war. On the contrary, cross-border cooperation has been deepened in all areas from economics over politics to people-to-people contacts. In 2008, the German border town of Flensburg put up the first bilingual signs.

The end of World War II was followed by the so-called retsopgør, the legal settlement regarding those who collaborated with the Nazis in Denmark. In 1943, five members of the German minority had formulated the so-called Haderslebener Declaration in the Danish city of Haderslev. It became the basis for the re-establishment of the German minority after World War II. Its key point: absolute loyalty towards the Danish state.

In the 1955, the Copenhagen-Bonn Declaration in 1955 provided a stable minority regime. The festivities regarding the 60th anniversary of these declarations have pointed out that the minority regime in the Danish-German border region is a story of success at all levels.

The European perspective offers a look at Poland. In Upper Silesia, where there historically has been a German minority, bilingual town signs were set up in 2008.

When will the time be right?

Despite all these developments, 2015 seems to be too early to add German versions to the town signs of four Danish towns. To be clear, bilingual signs have no legal or political consequences whatsoever. Bilingual town signs are purely symbols of psychological value. Seventy years after the end of World War II, sixty years after the Copenhagen-Bonn Declaration, the time is simply not right to set up bilingual signs.

When will the time be right?