NordSalt Blog Post #21 - July 2024

NordSalt Saltmarsh and Blue Carbon Quiz

Ready to test your skills and knowledge for the Nordic region and our project? Well look no further! Check out our quiz - share with your class, your friends, or maybe even challenge some of your peers!

- What proportion of the EU (Annex 1) saltmarsh habitats do the salt marshes in the NordSalt study area (Norway, Sweden, Denmark, Finland, Germany) represent?

A 25% B 35% C 50% - Which of the above-mentioned countries has the largest saltmarsh area?

A Norway B Sweden C Denmark D Finland E Germany - What is the most common salt marsh management practice in the region?

A Grazing B Harvest C Wild Nature - What has driven the major losses of saltmarsh habitat in the region?

A Overgrazing B Eutrophication C Drainage and diking - How does grazing affect the rate of organic carbon accumulation in Danish saltmarsh sediments?

A Grazing reduces it B Grazing doesn't affect it C Grazing increases it - What is the estimated current capacity for organic carbon accumulation by Danish saltmarsh habitats relative to Denmark’s greenhouse gas emissions (not considering the GHG emission from the saltmarshes)?

A 0.1% of emissions B 1% of emissions C 10% of emissions - To what extent does this support climate change (CC) mitigation?

A The CC mitigation corresponds to the correct answer above B Contributions to CC-mitigation would require expansion of the current sal marsh area and would depend on the net CO2 capture-effect of such action

Photo: Dorte Krause-Jensen

Dorte Krause-Jensen

Professor, Senior Researcher, Department of Bioscience - Marine Ecology; Arctic Research Centre

Aarhus University

NordSalt Blog Post #20 - June 2024

Viewing Nordic coastal marshes from space helps understand biodiversity patterns

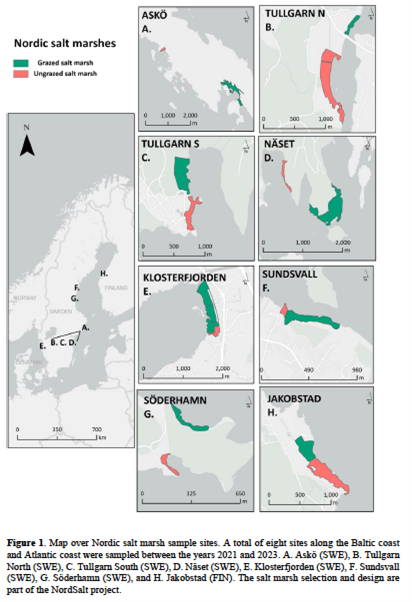

One of the main questions in NordSalt is how saltmarsh vegetation, and the role of these habitats as carbon sinks, is influenced by grazing. But many other aspects will also influence both the vegetation and the amount of carbon in the soil, which we’re interested in understanding better.

In 2023-24, Stockholm University student Annie Garnell has conducted a 60 credit MSc thesis project in landscape ecology, connected to NordSalt.

Fig 1. Annie Garnell, former MSc student at Stockholm University.

The idea was to position the continued NordSalt sampling in the summer of 2023 within the context of coastal landscapes, to assess how different spatial factors – like habitat size and landscape habitat composition – may also influence the unique vegetation in these communities, in addition to grazing. Past work in similar environments has shown that surrounding landscapes can be crucial for influencing the vegetation in coastal marshes. Particularly species richness and presence of specialized marsh plants appears to be partly determined by distance to other marshes, where increasing distance negatively affects the number of species found, because the marshes act as source populations that the plants spread between. And the further to a source, the less likely a species is to be able to spread there.

In summer 2023, Annie, her co-supervisor Dr Anaïs Richard and two German MSc students travelled around the Swedish and Finnish Baltic Sea coast and sampled vegetation communities in 5 pairs of grazed and ungrazed coastal marshes; at Klosterfjorden (in Halland, on the Swedish west coast), at Askö island (south-west of Trosa), outside Sundsvall and Söderhamn in the Bothnian Sea, and north of Jakobstad in Finland (Bothnian Bay). Annie also used data collected in 2021 in the Tullgarn nature reserve (south of Stockholm, Sweden), yielding a total of 15 paired sites (as one grazed site could not be sampled). In each site, a standardized survey of all plants within replicated 1m square plots was conducted, to assess the diversity and species composition of the vegetation.

Back in the office, Annie then utilized satellite images of each sampling area and in GIS outlined the edges and calculated the size of each of the marsh areas. The hypothesis to be tested was partly that larger marsh areas should house a larger plant diversity, because they are be able to house larger and (therefore) less vulnerable populations of marsh plants. Annie also estimated the composition of the surrounding landscape, estimating how much meadows, crop fields, forest, roads, housing, etc. that existed within 2km of each marsh area. The idea here was to assess whether certain types of surrounding land use categories appeared to influence the diversity of the vegetation.

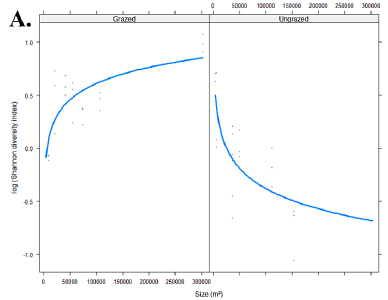

Fig. 3. The relationship between habitat size and plant biodiversity (the log of the Shannon Index).

Annie’s thesis contained more results than can be shortly summarized here, but one of the most interesting findings was the opposing influence of habitat size on plant diversity in grazed vs ungrazed areas. As expected, Annie’s data suggested that when comparing grazed areas, larger marshes housed more species per meter squared. This fits well with the idea of larger habitats being superior to small from a biodiversity perspective, possibly because they’re more easily colonized and/or may harbor larger (and more resistant) local populations. However, when comparing the 8 ungrazed marshes, which were all dominated by the common reed (Phragmites australis), the opposite pattern was found; the larger the ungrazed areas, the fewer the plant species were found in the plots. Our hypothesis is that the larger the ungrazed areas were, the further our sampling points was from neighboring habitats, that may function as source habitats for the less dominant plant species in the grazed areas, that one the one hand make up little of the overall biomass, but on the other hand make up most of the diversity. It is also possible that competition between the dominating reed strengthens with reed area extent; another size-dependent mechanism.

Analyses of this interesting data set continue, but Annie’s thesis clearly highlights the need to not only account for non-spatial aspects such as grazing when evaluating vegetation communities in Nordic coastal marsh habitats, but also account for factors relating to their position and size.

And as in other aspects of the world, bigger is not always better, it seems.

Johan Eklöf

Associate Professor, Director of Studies in Marine Biology

Department of Ecology, Environment and Plant Sciences (DEEP), Stockholm University

NordSalt Blog Post #19 - May 2024

Nordic saltmarshes embedded in the triple planetary crisis

In a statement to the participants in the high-level panel on biodiversity in Kunming, China and online on October 12, 2021, Josefa Cariño Taulí, head of The Global Youth Biodiversity Network (GYBN) asked delegates from states from all over the world the following question: "Who are we as human beings? And are we who we need to be? Who are you as decision maker - and are YOU who you need to be?" This statement was made with reference for the need of a new global biodiversity framework for protection of nature to follow the unsuccessful attempt the global community had made with the Aichi biodiversity targets for protecting biodiversity under the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD), the former of which expired in 2020 without any of its goals or targets having been reached.

The CBD was signed years earlier though, at the 1992 Rio Earth Summit by 150 government leaders, and recognizes that biological diversity is about more than plants, animals and ecosystems. It also includes food security, fresh air and water, shelter, medicine and more. The Convention focused on three separate but interlinked goals, namely a) the conservation of biological diversity, b) the sustainable use of its components, and c) the fair and equitable sharing of the benefits from the use of genetic resources.

Since that time, the concept of the world being in a triple planetary crisis has become more prominent and working in a silo is no longer possible – referring to three main interlinked issues that humanity currently faces and need to find solutions for, which in addition to biodiversity loss includes climate change and pollution. The interlinkages of these are well presented by IPBES when presenting the five direct drivers of change in nature with the largest global impact (ranked by impact) as: 1) changes in land and sea use; 2) direct exploitation of organisms; 3) climate change; 4) pollution; and 5) invasion of alien species. As such, and being cognizant of biodiversity not being protected in a vacuum, global leaders adopted the Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework (GBF) in December 2022 at the conclusion of the 15th Conference of Parties (COP) to the CBD.

In the GBF too, the link to the five drivers of change in nature and thereby indirectly the triple planetary crisis was referenced first in the background section, and then specifically in Target 7 (Reduce pollution risks and the negative impact of pollution) and Target 8 (Minimize the impact of climate change). For terrestrial and freshwater ecosystems, such as that of the Nordic saltmarshes, it is land-use change – #1 on IPBES list of direct drivers - that has had the largest relative negative impact on nature since 1970s, with the expansion of agriculture being the most widespread form thereof, using it for cropping or animal husbandry – coming mostly at the expense of other wetlands.

Given the persistent nature of plastics and its related toxicity, plastic pollution is also a significant threat to biodiversity in both freshwater and soil ecosystems and exacerbated by the identified indirect drivers of biodiversity change such as societal values and behaviors around production and consumption, population dynamics and local governance priorities. Within this pollution context, the United Nations Environment Assembly (UNEA) – the highest decision-making body globally for the environment - made history in March 2022 when it adopted a resolution that set up a roadmap to a an international legally binding instrument on plastic pollution by the end of 2024. In the Draft treaty text that was released to delegations prior to the meeting in Ottawa, Canada in April 2024, both the words “biodiversity” and “climate change” were mentioned 5 times each, demonstrating that here too, the link to the triple planetary crisis was known and understood.

Given that some estimates suggest that by 2050, if current trends continue, 20% of global oil consumption and an estimated 15-31% of the global carbon budget will be accounted for by the plastic sector alone, this link to climate change also presents itself naturally. The triple planetary crisis is similarly addressed within the United Nations Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) (commonly known as UN Climate Change). This convention, like the CBD, was also signed in Rio in 1992 and is tasked with supporting the global response to this threat. In fact, during COP28 in the United Arab Emirates in November-December 2023, the draft decision had five references to biodiversity such as:

“…Noting the importance of … the protection of biodiversity…[and]…Underlining the urgent need to address…the interlinked global crises of climate change and biodiversity loss.”

There is even a direct reference to the GBF in the decision of COP28 in the section on “Context and cross-cutting consideration” # 33. These links between global initiatives is critical; these global ambitions are what has to be translated into local realities for local governments across the world, including in local communities with the responsibility for governing areas that have Nordic saltmarshes. Exhibiting that these global arenas know that there is a link, is critical in that all three global agreements need and require reporting on area use, production and carbon credits (to name a few). The tensions between the three are also palpable – in that achieving goals in one may have a negative impact on another – such as that of the 30x30 target of the GBF – protecting and restoring 30% of all area globally – versus 55% cuts in emissions, which requires green shift in energy that requires both plastics and area. Being faced with these realities, local governments, with shorter time horizons that globally agreed agreements generally have, may be faced with more restrictions in their local governance moving forward. And reporting. There will be reporting! But with this cross pollination between global agreements, one may only hope that this translates to harmonization of reporting requirements as well.

Rachel Tiller

Chief Scientist

Fisheries & new Biomarine Industry, SINTEF Ocean AS

NordSalt Blog Post #18 - April 2024

Every new beginning comes from some other beginning's end

It is hard to believe that three years have passed since the NordSalt project kicked-off, in March 2021! Our efforts paid off, showcasing a successful collaboration of researchers with different backgrounds, working in five different countries to better understand and suggest improvements to protect, understand, and advocate for salt marshes and meadows in the Nordic region. The truth is though, this collaboration is more than three years old, and it doesn’t really end now…

This project was first born many years earlier, when various members of the core team came together to understand more than just one side and issue to Nordic salt marsh habitats. Engaging with people living at or near these environments, or understanding the differences across these habitats that span thousands of km , or even how biodiversity plays an integral role were just some of the unknowns the team would need to tackle. When the funding call opened from BiodivERsA on Biodiversity & Climate Change in 2019, our team got to work to submit a proposal that was ambitious and realistic, garnering the support of both EU and 5 different country funding agencies!

This month, each of the project teams highlighted findings, suggestions, and key things to continue to look into from their respective groups – you can watch the video here! You can certainly see the dedication shine through from each team in their explanations and understanding of the complexity of the project, but what you might not be able to tell is that each team engaged in new and unfamiliar practices to better understand their local (and other) Nordic salt marshes outside of their comfort zone (disciplines). Each team helmed the leadership on an important aspect of the research, ranging from biodiversity and plant life, to blue carbon sequestration and greenhouse gas emissions, to stakeholder engagement and communication, and even to mapping and classification differences across each country! It is hard to imagine our community engagement specialists putting on boots and collecting soil samples (Blog post #7), or our plant ecologists facilitating a meeting with stakeholders on perceptions of salt marshes at the intersection of human behavior (Blog post #6).

While the work officially continues for a few more months (and the next few years as we continue to share findings via published manuscripts, conference presentations, and future projects), our team put together a useful Policy Brief. In fact, this was an original promise from the NordSalt Project, and most of the team started out by saying ‘what the heck is a Policy Brief!?’ Luckily we have our experts within the team that helped everyone understand that a Policy Brief is a short, colorful summary of key findings and suggestions that is designed to inform and educate a broad audience. With pictures, quotes, and suggestions, this document is a tangible output that can be used as a primer or introductory document to anyone and everyone who wants to know more about Nordic salt marshes: what they are, why they are important, what we found out about them, and what we suggest moving forward to adjust our collective behaviors to manage and protect them. We balanced the perspectives from inhabitants (including animals and plants), farmers, tourists, and policy makers.

This document is just a snapshot of our work, and will need updating over time as we continue to learn more about these extensive habitats. It is meant to be used in government meetings, classrooms... and who knows, it could even make its way into your dinner conversation!

Jake Reardon

Project Manager

Faculty of Science, University of Southern Denmark

Gary Banta

Head of Department, Associate Professor

Department of Biology, University of Southern Denmark

NordSalt Blog Post #17 - March 2024

Will the new EU Nature Restoration Law help to brighten the future of coastal marshes?

While writing this blog post, the European Parliament voted for the Nature Restoration Law. The proposed legislation received a lot of resistance, and the final draft was significantly watered down from the original. The law passed by the European Parliament aims at restoring at least 20% of the European Union's land and sea areas by 2030 and all degraded ecosystems by 2050. Restoration will mostly happen on the Natura 2000 conservation areas.

The Red List of Habitats (2016) assessed the risk of collapse of all natural and semi-natural habitats, including three types of coastal marshes in the NordSalt area. Status for the coastal marshes varies depending on type, geographical location, and the level of data available.

A2.5b Baltic coastal meadows are endangered. Over the past 50 years, Denmark has retained approximately the same area of Baltic coastal meadows, but other countries have experienced substantial habitat loss. Finland has lost approximately 90%, Germany, 50-80%, and Sweden over 50% of the Baltic coastal meadow area compared to 50 years ago. In addition, the habitat quality has declined. The most significant threat to this habitat type is overgrowth following abandonment due to changes in traditional agricultural practices. Secondary threats include eutrophication, dispersed habitation, and marine water pollution. Thus, the main conservation measures involve restoration and maintaining the open habitat. As semi-natural habitats, Baltic coastal meadows cannot recover without human intervention, but suitable management practices can restore the quantity of the meadows relatively quickly. However, restoring the meadows' quality and regaining biodiversity will take several decades.

Distribution of coastal marsh habitat types in the NordSalt area according to the Red List of European Habitats (EU, 2016).

A2.5c Atlantic coastal salt marshes are vulnerable. Since 1960, the habitat quantity has declined in Denmark by 35%, whereas it has increased in Germany by 30-50%. Data is not available for non-EU countries. However, the decline is estimated to be less, for example, in Norway. During the same time period, quality decline occurred at rates of moderate (>30%) in Germany and intermediate (80%) in Denmark. The most significant pressures for these habitats include agricultural intensification, abandonment/lack of mowing, discontinuous urbanization, human-induced changes in hydraulic conditions, and invasive non-native species. The main conservation measures include maintaining the open habitat, restoration, establishing protected areas/sites, and regulation/management of hunting.

A2.5a Arctic coastal salt marsh occurs only outside the EU in the Arctic biogeographical region, for example, on the north coast of Norway. Very little data exists on this habitat type. The habitat was estimated to be stable over time, and there are no known present pressures causing area decline. However, rising sea levels can cause coastal erosion and changes in sea ice. Other possible pressures include increased industrial activities, offshore oil drilling, and pollution. Due to very low species diversity, the Arctic coastal salt marshes can be highly vulnerable to rapid environmental changes. Furthermore, they can be more vulnerable to rising sea levels than Atlantic coastal marshes due to the low organic production and inorganic sedimentation rates in flooded tundra along the Arctic coasts.

In the NordSalt project, we conducted an expert survey with 26 respondents, asking their opinions on the value and future of coastal marshes in their respective countries. The highest median scores for value were given by Finnish and Swedish respondents, while Danish and Norwegian respondents gave the lowest scores. Respondents' explanations highlighted coastal marshes as often overlooked habitats of which many people are unaware. When asked about the future of their country's coastal marshes, the majority expressed pessimism. In Denmark, 71% of respondents foresaw a bleak future, particularly if protection, management, and restoration actions were delayed, with concerns about rising sea levels and coastal squeezing. In Germany, 57% of respondents identified significant threats ahead due primarily to rising sea levels and coastal squeezing. In Sweden, 86% of respondents were pessimistic due to changes in agricultural practices, declining number of grazing animals, and rising sea levels. A Norwegian respondent expressed a desire for more attention to coastal marshes. However, 75% of the Finnish respondents viewed the future positively for coastal meadows. Finnish optimism was based on increased resources directed towards coastal meadow management and restoration and expanding Baltic coastal meadow areas in the country.

Cattle grazing keeps the landscape open and vegetation short and diverse on a coastal meadow in Houtsala, S-W Finland. The area at the back, behind the boat house, has been grazed before but is now overtaken by common reed. Photos by Mikael von Numers.

It is ironic that the coastal marshes are most valued in Finland where the majority have already been lost. Fortunately, there are still some coastal meadows left in Finland and others that can be restored. Finnish respondents were pleased with the ongoing Helmi Habitats program (2021-2030, Ministry of Environment), which aims to strengthen biodiversity by advancing the management and restoration of habitats like coastal meadows. Results are beginning to emerge: 4000 hectares of coastal meadows in Natura 2000 areas in the Bothnian Bay are now being managed. Clearance of bushes and reed beds, along with the start of management by grazing or mowing, is improving the habitats of several endangered species of birds, plants, and insects. For example, the nesting population of critically endangered ruff (Calidris pugnax) has doubled in the area in ten years.

We will see how the new EU Nature Restoration Law will influence the future of coastal marshes. Hopefully, the turn to optimism will happen soon in all countries. The respondents' bleak assessment of the value of these habitats carries a hopeful message: if coastal marshes are undervalued due to a lack of awareness, we can all contribute easily. And projects such as NordSalt can have a significant impact!

Anu Vehmaa

Project researcher

Environmental and Marine Biology, Åbo Akademi University

NordSalt Blog Post #16 - January 2024

The Nordsalt Mesocosm Experiment retired!

So the day had come when we had to disassemble the NordSalt mesocosm experiment. I faced this day with one crying and one smiling eye. The mesocosm experiment became the place where I spent most of my time outdoors during the summer of 23 - even camping next to it for a 72-hour measurement campaign. And I can say that working in the mesocosm experiment was not bad at all. On hot days the occasional flushing of the rubber boots cooled down from below, on rainy days I could easily stick an umbrella into the dome construction to stay dry, and on cold days I could quickly go inside to warm up with a cup of tea. Pretty friendly working environment when compared to field work. I can conclude that the whole facility became an important habitat in which I naturally occurred.

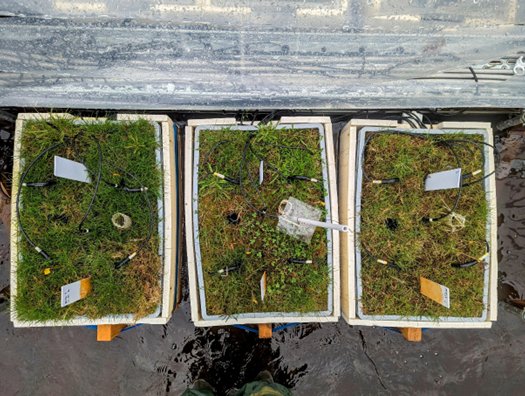

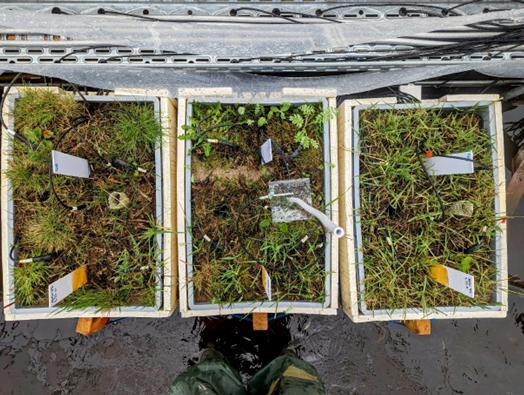

Figure 1 - help yourself out on rainy days

The mesocosm experiment was set up in early 2022 and the warming treatment started in June 2022. We studied three different soil origins (Finland, Sweden, Denmark) from grazed and ungrazed Baltic coastal wetlands, to gain insight into how warming will affect the carbon cycle and plant response in these important blue carbon ecosystems. To do this, we installed an intelligent, feedback-controlled heating system that increased the temperature in steps of +1.5°C up to +6°C below and above ground.

During the two growing seasons we collected an extensive data set, including data on redox potential, decomposition, vertical accretion rate, above-ground biomass, greenhouse gases and the development of individual species. Now, with the completion of the project and the possibility of destructive sampling, not only attracted the NordSalt team to return for a visit but also sparked spontaneous interest among the working group in Hamburg. The NordSalt team was represented by partners from Finland, Denmark and Sweden. The ambitious goal of sampling each heat treatment not only kept the NordSalt team working long days, but also kept me and my colleague Julian Mittmann-Göttsch - who luckily decided to sample the soil for microbial analysis - on a tight schedule.

After an urgent email from Prof. Dr. Kai Jensen asking for more help in the working group, the team grew and suddenly there was hustle and bustle around this rather quiet experiment. There is something magical about working with a team. It's a lot more fun and even though it's a bit stressful to coordinate more people, I enjoyed the time and especially the nice coffee break.

After a full week of sampling the soil for microbial, C/N, grain size, pore water analysis, belowground biomass and many more variables, we not only completed the sampling campaign successfully but also left behind soil blocks that look like Swiss cheese.

After a full week of sampling the soil for microbial, C/N, grain size, pore water analysis, belowground biomass and many more variables, we not only completed the sampling campaign successfully but also left behind soil blocks that look like Swiss cheese.

So thank you to the whole team involved for giving this wonderful experiment a proper send-off.

Figure 4 - Team leader Gary taking some final samples from the plot

If you want to read more about the NordSalt Mesocosm, check out blogpost #05 and #12!

Ella Logemann

PhD student, Applied Plant Ecology

Institute of Plant Sciences and Microbiology, Applied Plant Ecology, University of Hamburg

NordSalt Blog Post #15 - September 2023

Blue carbon science - rise and grind!

In classic dictionaries, the verb “to grind” is to reduce something to powder or small fragments by friction (as in a mill or with the teeth). A more modern, slang meaning is to persevere when doing something hard (difficult, repetitive, physically or mentally demanding) to attain a certain goal. This has in turn given rise to the popular meme “to rise and grind” – acknowledging (even being proud of) the need to get hard/boring work done to get the desired results.

In many blue carbon projects like NordSalt, both meanings of grinding are central, which our excellent team of NordSalt Sweden field and lab workers can attest to. Postdoc Anais Richard (Stockholm University), master students Annie Garnell (Stockholm University), Katrin Möller and Beke Eichert (Hamburg University, Germany), and lab assistant Nadja Halltin Nijm (Stockholm University), worked tirelessly in the field during five tough weeks this summer to sample plants and soils across five pairs of grazed and ungrazed coastal sites along the Nordic coastline from Klosterfjorden on the Swedish North Sea coast in south-west, to Karleby on the Finnish side of the brackish Bothnian Bay to the north-east. The aim was to complement the sampling done in 2021 and cover a larger fraction of the Baltic Sea climate and salinity gradient.

The hard work of soil coring

In each site the team surveyed plant communities and took soil cores in 3, 1x1m plots; a task that may sound easy, but that in reality is hard both mentally and physically. Because most sites were situated within nature reserves with sensitive wildlife and access restrictions, the team could not use motor-driven corers and instead had to rely on hand force (hammering, pulling). Each site also presented different obstacles in terms of soils either being very dry and hard (especially during the dry June 2023), or being very wet and therefore difficult to sample later on in summer, or being very sandy (falling apart), or even made up of gravel. Often the team had to try several coring methods and discard damaged cores before they actually had intact and usable cores – which alone could take hours of hammering, pulling and shoving in hard field conditions (strong sun/rain/wind, mosquitos, etc.).

Grinding away in the lab

Much ecological work is about doing a simple task over and over again, where it’s the repetition and need for maintained accuracy and preciseness that makes it difficult. Currently, this is being experienced by the team of NordSalt staff processing samples in our lab. First, the plant roots and soil must be separated by hand so that we can estimate their individual carbon content; a process that can take several hours per sample. With ca. 160 samples, this step alone equates several months of work. Then, the dried soil and plant samples must be grinded, sometimes by hand with a mortar and a pestle, before the carbon content can be estimated. With both plant and soil samples from each soil slice, this equates to >300 samples to grind.

While eagerly awaiting the results from this and earlier summer’s field and lab work, I – the leader of the biodiversity work package of NordSalt – finish this blog post by expressing how grateful we are to all the staff and students for their hard work, which is needed in the end to get the sought after values of carbon content. Rise and grind!

Johan Eklöf

Associate Professor, Director of Studies in Marine Biology

Department of Ecology, Environment and Plant Sciences (DEEP), Stockholm University

NordSalt Blog Post #14 - August 2023

Unlocking the Secrets of Danish Saltmarshes: Nature's Carbon Storehouses

In this blog post, we're taking a closer look at the blue carbon potential of Danish saltmarshes. The research was conducted along the beautiful coastline of Denmark, where various research endeavors, including the NordSalt project, have shed light on this ecological phenomenon. Our aim was to unravel how much carbon is currently stored and annually accumulated within these marshes, uncover the driving factors behind this process as well and draw comparisons with saltmarshes worldwide.

After going deep into the soil of 17 different Danish saltmarshes, we found out that every square meter of Danish saltmarsh stores around 10 kilograms of carbon in the top meter of soil. The top 30 cm of soil, which can be more unequivocally attributed to the presence of the saltmarsh stores 5.8 kilograms of carbon per square meter, an amount that has been accumulated over more than 100 years. And that's not all – these marshes are also locking away approximately 31.5 grams of carbon per square meter each year.

An ungrazed saltmarsh located in Als, along northeast coast of Denmark. (c) Carmen Leiva Dueñas

There are of course spatial differences, with some lush saltmarshes in Odense, Nibe, and Als, standing tall with higher carbon stocks and accumulation rates. On the flip side, there are quieter players like Bøjden, the enchanting Wadden Sea, and the northern stretch of Zealand, offering a bit less carbon storage. But what sets these marshes apart? Let's uncover the ingredients that make a marsh a pro at carbon storage and accumulation. Think of it as a recipe – the right mix of ingredients. Soil type, marsh age, and the origin of organic matter all contribute to this natural carbon-saving magic. It's like an open secret now. For your saltmarsh to outperform, you need mud and the longer the marsh has claimed its spot without erosion scars, the better. Do not forget the thriving saltmarsh plants, and a touch of marine influence from neighboring eelgrass meadows. These ideal conditions often come together in sheltered corners, creating the perfect carbon storage stage.

Surface soil from a saltmarsh core collected along the Danish coastline. (c) Carmen Leiva Dueñas

While not a must-have, this next ingredient contributes extra carbon to the soil. The adorable cows that roam and graze these marshes appear to play a role. While additional data is required for full confirmation, it seems that cows, with their stomping around, create conditions that slow down the breakdown of carbon.

When we look at Denmark's saltmarshes alongside their Northern European counterparts, something intriguing pops up: our marshes seem to be a bit more laid-back when it comes to trapping and storing carbon. We found out that our young saltmarshes and their tendency to hold less carbon extend not only to Denmark but also to close neighboring regions, particularly along the Wadden Sea and the Southern Baltic Sea. This could be attributed to the Baltic's relatively recent geological history and Denmark's changing sea levels over recent times. These factors have certainly left their mark on the development of these saltmarshes.

Let's take a step back to grasp the significance for climate mitigation of the collective carbon accumulation potential within Denmark's saltmarshes. Despite covering just 1% of the country's land, these modest marshy zones capture roughly 0.1% of Denmark's annual carbon emissions, a number that could double to 0.2% if their historical expanses were restored. While this might seem modest, it's important to recognize that every contribution matters. Moreover, it's crucial to remember that for this impact to materialize, it must go in tandem with the phasing out of fossil fuels. Swiftly decarbonizing our society is paramount to shield these marshes from further loss caused by intensifying storms and rising sea levels, all stemming from the current climate change.

Before we finish, remember this – saltmarshes are more than just carbon storage units. They're like nature's multi-taskers. Apart from their carbon-capturing skills, they provide homes for various wildlife, act as a buffer against coastal erosion, and offer serene spots for relaxation, among many other ecological services. While saltmarshes might not be the ultimate carbon warriors, every bit of carbon they store is a step in the right direction. These marshes deserve our love and protection, not only for their carbon storage but for all the other goodies they bring to the table.

Next time you stumble upon a saltmarsh, take a moment to appreciate their quite activity – storing carbon, supporting biodiversity, and adding a touch of natural beauty to our world.

Carmen Leiva Dueñas & Dorte Krause-Jensen

Department of Ecosciences, Aarhus University

NordSalt Blog Post #13 - June 2023

Under your feet

As the newest member in the Swedish team, I would like to introduce myself and share with you my integration into the NordSalt project. I come from France and I did my PhD at the marine research station of Arcachon (Bordeaux University). I am a benthic ecologist who mainly worked on intertidal mudflats so far.

I studied the effect of benthic macrofauna activity (their bioturbation) on biogeochemical fluxes at the sediment water-interface (oxygen and nutrient) and on microphytobenthos (MPB), which are an association of microscopic, unicellular, and photosynthetic organisms living at the sediment surface. These benthic primary producers play a key role in coastal ecosystem functioning, especially being an important resource for benthic and pelagic food webs. However, coastal environments are dynamic, complex and subject to strong anthropogenic pressures. So, to better understand the benthic compartment functioning, we did some experiments to better know and quantify the factors controlling MPB dynamics. Especially, the influence of macrofaunal bioturbation was poorly known in the literature, contrary to the temperature for example. The bioturbation refers to the sediment/soil mixing induced by a biological activity. This process includes both sediment reworking (the mixing of sediment particles) and bioirrigation (the movement of pore water and solutes through the sediment matrix). The aim was to understand if the macrofauna stimulate the MPB through the increase of nutrient release thanks to their bioirrigation or if their impact were more negative due to their grazing and sediment mixing activity which mechanically disrupts the MPB. As you can guess, the answer is not easy and it’s a question of balance between lots of parameters!

So why am I interested in working in the Nordsalt project? Because it's close to my research topic, but in a slightly different habitat, with ecological processes taking place on a different scale of time and space. NordSalt allows to understand the functioning of the Nordic salt marshes in their globality, which is still poorly studied. That's one of the first things that really got me excited: to be part of the discovery of how a particular habitat works, especially in the Nordic regions!

First of all, in the Baltic sea, there are no tides like on the Atlantic coast, which changes the land-sea gradient and results in a different ecological functioning. There are also differences in temperature, ice cover and, above all, salinity. In fact, there is a strong salinity gradient in the Baltic Sea: the further you move away from the Danish Straits, the lower the salinity. This has a major impact on the type of vegetation and on the quantity of oxygen dissolved in the water, which will modify the decomposition processes of organic matter in time and space, and modify the fluxes of carbon and methane especially. These fluxes are studied in the project as they are of major importance in the context of climate change. That's the second thing that attracted me: the fact that there's a biogeochemistry aspect, focusing on carbon, all in a context of global change. Given the urgency of the current situation, trying to find solutions to better manage salt marshes and thus mitigate the effects of climate change is extremely gratifying.

And what about bioturbation? It's also presents in this project! By studying the effect of grazing on different plant species and on carbon storage in particular, bioturbation is hiding behind the trampling of soil by animals. What's more, in ecosystems involving plants such as this one, and not microalgae, bioturbation is also hidden in their root systems... in fact, roots have air-filled tissues and allow the creation of pores in the sediment/soil. This facilitates water infiltration and deep oxygen diffusion. This process is indirectly studied by looking at the link between the quantity of roots and the quantity of carbon stored in soils. Finally, what really appealed to me was that there was a primary producer aspect, through plants and their biodiversity. They play a central role in any ecosystem, not only by being at the base of the food chain, but also because they can influence carbon flows and thus be the key to a greener future.

This summer I will take part to the Swedish team to do more field experiments all along the coast to try to catch up the salinity gradient in the aim to better understand the effect of this factor on plant diversity, soil stability and carbon storage. So, next time I will come back with some pictures!

One more thing: Be careful when you walk… don’t bioturbate the soil too much!

Anaïs Richard

PostDoc, Department of Ecology, Environment and Plant Sciences (DEEP)

Stockholm University

NordSalt Blog Post #12 - March 2023

NordSalt mesocosm experiment – Releasing the experiment from hibernation and protecting it from unwanted visitors

Do you remember the Nordsalt mesocosm experiment we introduced to you some time ago (see ‘NordSalt Blog Post #05 - December 2021’)? Well, we have an update for you. Since June 2022, when we started the experimental warming, we've been conducting a series of measurements to understand how warming affects the plant and soil-related processes in mesocosms, sampled from grazed and non-grazed salt marshes across Finland, Sweden, and Denmark. To achieve this, we've heated our mesocosms by up to 6°C above the ambient temperature, both above and below ground! Our observations have included monitoring the development of species diversity, gas emissions (methane and carbon dioxide), and root growth rates.

As winter approached, we partially put the experiment into hibernation mode. Why? Because during the winter months, most of the (for us) relevant biological processes are soil-related and not as much related to aboveground processes. So during this time, we activated only soil heating and inactivated the above heating from infrared radiators. The latter are the main power consumers, so a very nice side-effect was that we were able to significantly reduce the experiment’s energy consumption.

Simon re-installing the infrared radiators, plant perspective

Now that winter is over, we’re observing the mesocosms coming back to life. The grass in the samples from grazed sites is already looking pretty green, and also in non-grazed mesocosms freshly sprouting plants can be observed. That, of course, also means that all infrared radiators have been re-installed and above heating has been turned on, and we can now start taking measurements related to aboveground processes again!

Non-grazed mesocosm from above, scientist perspective

Grazed mesocosm from above, scientist perspective

But, the hibernation period wasn't without its challenges! Earlier this year, a pair of geese started to visit the experiment pool quite frequently, and also a pair of ducks, probably from around, became very much interested in our experiment. These birds were strongly suspected to be very interested in the consumption of fresh and young phragmites sprouts!

Fresh Phragmites sprouts, desired perspective of the geese

Now, we don't want to begrudge our feathered friends a tasty snack, but we also don't want them messing with our data. To prevent the geese from dining on the phragmites, we decided to approach the problem in a very German way: we installed a fence! Since then, the geese have not been seen again (probably they have moved to some easier accessible green pastures) and the vegetation in our boxes can continue to grow undisturbed, only affected by some additional heat coming from above and below.

A sprout-interested goose, experiment perspective

The NordSalt mesocosm experiment, from goose perspective

(All photos have been taken by me, except for the one showing the goose)

Simon Thomsen

Faculty of Mathematics, Informatics and Natural Sciences, Department of Biology

Institute of Plant Sciences and Microbiology, Applied Plant Ecology, University of Hamburg

NordSalt Blog Post #11 - February 2023

Being FAIR with our NordSalt data

One of the most valuable things in a research project is the data obtained from field samplings, experiments, surveys, etc… That is why it is so important to consider data during the early stages of a project. More and more data management has been prioritized within projects, and concepts such as the FAIR concept has gained attention within the scientific community. The FAIR concept argues that all primary data from research projects must be Findable, Accessible, Interoperable and Reusable to be later shared with the scientific community, practitioners, managers and decision-makers, an essential requirement from most funding agencies today.

SangyaPundir / CC BY-SA (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0)

To make our data FAIR to other users, we first must ensure data fairness within our group. This is especially true in a project like NordSalt, where researchers from distinct nationalities, speaking different languages and with diverse backgrounds are working together. Add to it a huge amount of data, in the most distinct kinds of file extensions, being collected across distinct areas and that will need to be integrated and analyzed together, so we can provide a full picture of the coastal marshes in the Nordic area. Thus, the adoption of FAIR practices is essential so we can understand each other!

Here are some good data management FAIR practices that we have adopted:

Findable: we use platforms such as TEAMS as an initial data repository within our group. Storage and management of archives in distinct sub-folders make sure that the data is easily Findable by the NordSalt researchers. Data archives also have meaningful names with the identification of their source area, version control and users.

Accessible: all our data are stored in files extension that can be accessed through free software and by anyone with permit to access to the project’s restricted platform. Importantly, any sensitive data, as personal data from interviews, are used and protected according to the General Data Protection Regulation from the European Union.

Interoperable: we strive to use standardized spreadsheets, with data and metadata vocabularies to store all primary data, so datasets will be easily understood and used among our teams. English is our data working language – it seems obvious but that’s not always the case so it is best to clarify.

By aiming at the practices described above, we are making our data easily Reusable within NordSalt. At the same time, we are preparing data to be deposited in large data repositories such as Zenodo when the project is finished, when extra steps to enhance their fairness such as DOI assignments, license of use and enriched metadata will be taken. Following best practices for data management now prevent headaches later, and grants FAIR access to the public, our stakeholders who will also contribute to the understanding and management of Nordic coastal marshes.

Marianna Lanari

Postdoc

University of Southern Denmark

NordSalt Blog Post #10 - January 2023

Are citizens willing to pay for ecosystem services?

In the fall of 2022, we surveyed 1000 respondents in each of the countries participating in the NordSalt project: Denmark, Finalnd, Germany, Norway, and Sweden. The purpose of the survey was to evaluate citizens’ willingness to pay for ecosystem services. The results of this survey will be published in a journal article in the Spring of 2023 and shared via the NordSalt communication channels. Keep your eye out!

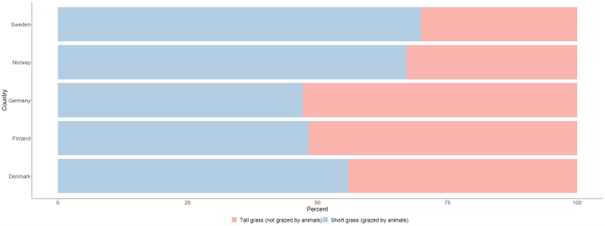

As much of the research conducted in the NordSalt project focuses on the differences between grazed and ungrazed salt marshes, we thought it would also be interesting to examine public perception regarding grazing. Grazed and ungrazed salt marshes provide different services to the public; ungrazed salt marshes, for instance, are much easier to walk on.

In the survey, respondents were presented with the following two images: a salt marsh with short grasses (grazed by animals) and a salt marsh with long grasses (not grazed by animals). They were asked: “If you could have one of these salt marshes near where you live, which one would you choose.“

Example of a grazed salt marsh (above) and ungrazed salt marsh (below)

Interestingly, we see some country differences. In Sweden, Norway, and Denmark, a majority of respondents would prefer to have a grazed salt marshes near where they live, whereas in Germany and Finland a small majority would prefer to have an ungrazed salt marsh near where they live.

In the article on the survey, we will delve further into citizens’ views on salt marshes. For instance, what makes citizens willing to pay for salt marshes, and are they willing to decrease their house value, be personally inconvenienced, or pay extra taxes to manage and conserve these important habitats?

Anne Gaspers

Master of European Studies

Climate & Environment, SINTEF Ocean AS

NordSalt Blog Post #09 - December 2022

Putting coastal habitats into boxes

People have a need to put things into boxes, and habitats are not an exception. Historically, habitat classifications have been developed for a specific area, for a particular scale, and for a specific purpose by managers and researchers who need and use them. Today, classifications are used mainly for administrative purposes, such as mapping or management, but also in science. The result is a plethora of classification systems that at least partly overlap.

At the end of September 2022, 16 researchers and managers gathered in Turku, Finland, to discuss the classification of salt marsh and coastal meadow habitats in the Nordic region. The 2-day workshop had participants from all five NordSalt countries (Denmark, Finland, Germany, Norway, and Sweden).

The workshop's main aim was to assess whether the current European classification systems are sufficiently operational for describing and managing Nordic coastal marsh habitat extent and diversity. The EU Habitats Directive, Annex I habitat classification (Natura 2000 habitats), is in use as the primary system for these coastal habitats in Denmark and Sweden. In Finland and Germany, where more detailed national or regional classifications are used, the habitat classes can be traced back to the Habitats Directive. There is also another European classification system, the EUNIS habitat classification, which is meant to be a comprehensive pan-European system for habitat identification. However, at least for now, it is not used by any workshop participants. As a non-EU country, Norway has its own classification system, which is not connected to the EU-wide classifications.

The participants agreed that there is a need for harmonization of classification systems within and between countries, especially in the Baltic Sea area. They also mentioned that the habitat descriptions should be more detailed for management purposes. For example, the class 1630 Boreal coastal meadows is too broad to describe the variety of the Baltic Sea coastal meadows. Perhaps, the habitat class should have subtype(s)? More detailed, new subtypes could have positive consequences and increase interest in these important habitats.

The participants also discussed ways to improve habitat management and mentioned the need for proper monitoring several times. The EU member states are required to report on the status of the habitats mentioned in the Habitats Directive every six years. As the main objective of the directive is to maintain and restore a favorable conservation status for these habitat types, the reporting is supposed to capture their contemporary status and trends. However, the EU does not give instructions on how the monitoring should be implemented. Thus, monitoring practices are versatile, and there is space for improvement.

Habitat management needs to be based on information that is up to date. Regular long-term monitoring is especially essential when climate change modulates the habitat drivers; the former management practices might not work ideally in changed conditions. Naturally, habitat mapping and monitoring require resources, and the quality of collected data correlates with the availability of resources. However, there are ways to collect good-quality data without massive resources. Remote sensing, such as aerial photos and satellite images (e.g., CORINE Land Cover), are valuable tools for monitoring. Furthermore, certain classification system features, such as modularity, can save resources. Therefore, the monitoring strategy and the classification system should be linked together.

But can we get rid of the boxes someday? Open data and big data analysis may slowly replace traditional habitat classifications. Perhaps in the upcoming decades, even a salt marsh specialist can stand on the shore and admire the diversity of these coastal habitats without wondering if they are typical examples of the habitat type.

Anu Vehmaa

Project Researcher

Åbo Akademi University

NordSalt Blog Post #08 - November 2022

The hunt for salt marshes in Norway

A salient feature of NordSalt is not only interdisciplinarity but also internationality. People of different nationalities and disciplines come together to work on one topic: salt marshes. This time project partners from four institutes from three countries gathered in Trondheim, Norway to investigate this coastal ecosystem.

One may ask: “Are there any salt marshes in Norway? The country of fjords and steep coastal transitions?” And indeed, the Norwegian Team itself was surprised when in the year 2020, Borgersen et al. revealed that there are actually salt marshes in Norway.

Norwegian salt marshes are understudied; there are a limited number of publications regarding salt marshes and their importance in Norway.

When Team Hamburg, with long-standing expertise in salt marsh plants and old personal connections to Norway, heard of Norwegian salt marshes, they were excited to explore them. We scheduled a sampling trip to Norway. Thought was put into planning, packing lists were created, and the material was organized with one question overshading the enthusiasm of the whole campaign: Will we actually FIND salt marshes? This also led us to the main challenge: ‘the saltmarsh identification’. As the previous post already stated, the Norwegian social scientists from NordSalt are willing to dip their toes into new waters. This feature and their position in Trondheim pressured them to take over the challenge of salt marsh identification. In other words: We biologists expected our job to be done by them.

The social scientists, Lacie and Anne, started to explore nearby salt marshes. They investigated these ecosystems during the winter of 2022 and collected grass for further identification. As a biologist, I have to point out, that identifying plants usually happens when the plants are still active and green, meaning during summer. Nonetheless, the two brought old, dead grass and pictures to an in-person team meeting in Hamburg in April 2022. At the meeting, they asked us ‘plant people’ if we could identify the plant and if it could originate from a salt marsh. We answered: ‘There are chances, that it actually could’.

Lacie took care of the accessibility and permit for the field sites while Team Denmark made sure we had all the needed equipment in Norway.

Half a year later, our travel started, based on the previously described information and blind trust in the social scientists having spotted the right ecosystem. The natural scientists flew in from Denmark and Germany, still with doubt that we would be successful. The excitement increased while the uncertainty stayed consistent. Finally, we arrived at our first field site. Lacie - feeling in charge and being especially excited – announced, “Okay we are here.” Silence. All holding their breath while looking at a beach ridge or possibly a dune-like landscape. Kai and me looking at each other, scared looks on our faces. Nonetheless, optimism took us further inside the ecosystem. After crossing the dry beach ridge on sand and pebble stones, we saw a wetland in a depression close by. The hope increased. Then without caring about getting wet feet, we went deeper inside and finally, we had our relief. We were standing on Juncus gerardii - a grass which is typical for salt marshes. And the closer we looked into the vegetation, the more typical salt marsh plants we found.

So YES, we have found salt marshes in Norway… and also sampled them!

And with that: Shout out to our social science colleagues for making this possible and hosting our stay!

Ella and Kai

Ella Logemann

PhD student, Applied Plant Ecology

Institute of Plant Sciences and Microbiology, Applied Plant Ecology, University of Hamburg

Kai Jensen

Head of Research unit, Faculty of Mathematics, Informatics and Natural Sciences, Department of Biology

Institute of Plant Sciences and Microbiology, Applied Plant Ecology, University of Hamburg

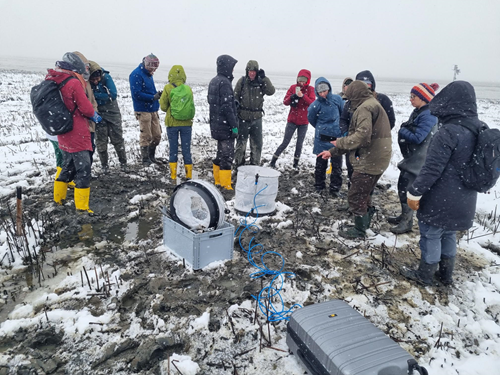

NordSalt Blog Post #07 - April 2022

Dipping your toes into new waters and creating common understanding in interdisciplinary work

On 31 March 2022, I, a social scientist, donned a pair of borrowed rubber boots and made my way out into a salt marsh in Hamburg, Germany with other members of the NordSalt project consortium, mostly biologists and ecologists. The goal was to make greenhouse gas flux measurements. The NordSalt project assesses the nature, diversity, extent, and long-term changes of Nordic coastal marsh habitats, and greenhouse gas measurements are just one of the project’s many activities. But what was I, a social scientist who usually spends her days planning and executing workshops and designing surveys, doing in the field?

I'm dipping my toes - well, my whole foot - in!

I'm dipping my toes - well, my whole foot - in!

NordSalt is a perfect example of interdisciplinary work. The social science work, stakeholder engagement through workshops as well as a public perception survey, is well-integrated into the entire project, complementing the work conducted by the biologists and ecologists; it’s even placed in the project’s first work package. In the project, researchers often try on different hats – or in this case boots, with the social scientists taking part in field work and the biologists and ecologists helping to conduct workshops. With the European Union’s focus on stakeholder engagement in the Horizon Europe framework program, more and more projects receiving EU funding will be interdisciplinary – like NordSalt – mixing together social scientists with biologists, chemists, physicists, engineers, etc.

According to NordSalt Project Leader and Head of the Department of Biology at the University of Southern Denmark, Gary Banta, this type of interdisciplinary work can be highly beneficial, though it, of course, comes with its own set of challenges. As Banta states, “If you’re looking at how to understand and solve a “problem”, if you can use that word, you need to approach it from more than one angle, one discipline.” Looking at problems from different disciplines provides a more holistic understanding. While the benefit of interdisciplinary work is greater understanding of the problem at hand, the challenge is finding common understanding. “You have to work at developing a common language of understanding, and you have to learn to understand and respect other scientific disciplines when working in an interdisciplinary way” Banta states.

The NordSalt team setting up GHG equipment - rain, sun, or snow!

The NordSalt team setting up GHG equipment - rain, sun, or snow!

So, what makes interdisciplinary work, well, work in the NordSalt project? While all specialists within our own disciplines, we are not afraid to cross-over and take on new roles. At the project meeting, I donned the rubber boots and dipped my toe into the salt marsh, literally. Being part of measuring greenhouse gases and looking at the different warming experiments conducted to see how salt marshes respond to climate change, provided me with a greater understanding of the problem at hand. I take with me this understanding as I analyse the results of the workshops and create the public perception survey. While I will never be an expert in salt marsh research – that’s not my field – working side-by-side of the people in the projects who are, very much, experts in the field is important for my work in the project. Not everyone can participate in every meeting, in every experiment, but it is important to include researchers from different disciplines in activities that may not at first seem relevant for them. Dipping your toes, so to speak, into each other’s work creates a common language, and this common language is necessary for well-functioning and truly interdisciplinary work.

Anne Gaspers

Master of European Studies

Climate & Environment, SINTEF Ocean AS

NordSalt Blog Post #06 - March 2022

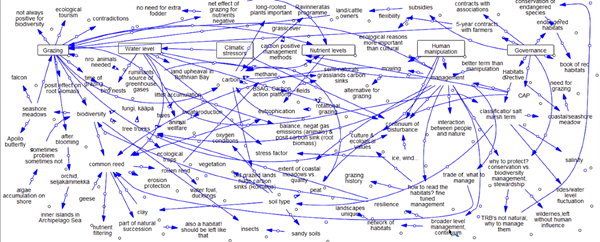

Multi-actor Labs - Lessons Learned across research disciplines

One of the challenges the NordSalt project wants to tackle is bridging gaps between scientists, decision-makers and society. How can we translate our ecological results into meaningful information for governance and users of these coastal habitats? To do so, the NordSalt project has run workshops (also known as Multi-actor Labs) with stakeholders using a standardized methodology to get insights on their perceptions and thoughts on Nordic salt marshes across its 5 study areas.

The MAL coordinating team in Denmark

MALs in Norway:

The Norwegian MALs kicked off the NordSalt partners' MAL round in January 2022, and was organised with experts in the fields of governance and management, together with some project partners. The MAL was a great springboard into the topics at hand, and led to a discovery not only of what we do know about salt marshes in Norway, but also what we don't. This gave us renewed fuel to drive the project further, and helped to validate the work we are doing.

The MAL coordinating team in Norway

The MAL coordinating team in Norway

Overall the experience was very fun and informative, leading to informal but highly beneficial conversations. In addition, it was a great opportunity to interact with and build a solid network of important players within the topic, which can be an invaluable resource for further research and possible implementations.

Lacie Setsaas

Communication Adviser

Management & Staff, SINTEF Ocean AS

MALs in Denmark:

In Denmark, Multi-actor labs took place in February and March led by the NordSalt team in Denmark (SDU and Aarhus University researchers) with the support of the SINTEF team from Norway. We combined in-person and online meetings to discuss with stakeholders from different sectors such as researchers and representatives of NGOs, private foundations, companies, and distinct levels of governance.

The MAL team in Denmark, in action!

During our informal meetings, we discussed environmental drivers affecting Danish salt marshes and their potential as nature-based solution in face of the climate changes among other things. From our enthusiastic participants, we learned about the challenges of managing these habitats under current environmental regulations and national jurisdictions. We also discussed the use of these marshes and coastal meadow as well as the ecosystem services that should be prioritized from their points of view. According to the participants, coastal protection against extreme weather events and sea level rise and biodiversity maintenance are key services provided by Danish marshes. Importantly, we also learned that salt marshes management and conservation must consider the societal and economic demands involving these coastal habitats.

Running the Multi-actor labs was a very enriching experience for the NordSalt team in Denmark where we could interact, learn from and strengthen partnerships with key players at local, regional and national levels. We look forward to sharing our results with them in the next round of meetings! By working with the SINTEF team, we have also been learning the importance of transdisciplinary studies and how to get out of our “scientific bubble” to engage with stakeholders and produce policy-relevant knowledge!

Marianna Lanari

Postdoc

University of Southern Denmark

MALs in Finland, 21-22 February 2022

Multi Actor Labs in Finland took place on two consecutive days in February 2022. Both workshops had seven participants representing, for example, governmental institutes, such as the Ministry of Environment, Finnish Environment Institute, Natural Resources Institute Finland, as well as universities, farmers, and NGOs, such as the Baltic Sea Action Group and the Water and Environment Association of Ostrobothnia. The workshop was organized by Christoffer, Mikael, and Anu (Åbo Akademi University), and Anne (SINTEF Ocean AS, Norway) was helping with the modeling methods.

The workshops were held online due to the prevailing COVID-19 situation. The biggest concern that we had beforehand, was how the process would work online, and if the discussion would be fluent and relaxed. We worried for nothing; the discussions were lively, multifaceted, and full of information.

It was clear that the participants loved to talk about the coastal meadows, their management, biodiversity, and especially grazing. Many of them are real coastal meadow enthusiasts! In addition to the professional interest, these experts are actively working for the good of the meadows during their free time through, for example, the Cultural Landscapes Association.

The mapping event from one of the Finnish MAL workshops. So much to discuss!

The workshop discussions taught us that grazing is a much more multifaceted management method than we would have ever guessed. Season, area, number of grazing animals, type of animals, grazing intensity, rotation of grazed meadows, water level, soil type, just to name a few, are variables that must be considered when planning optimal management of the site. Even though the motivation for management might not be the same for farmers, environmentalists, or local communities, there seems to be a consensus that well-planned grazing can lead to results that favor all: high biodiversity, beautiful landscape, and healthy grazing animals.

Anu Vehmaa

Project Researcher

Åbo Akademi University

NordSalt Blog Post #05 - December 2021

Salt marshes and global change - the heat is on!

One of the aims of NordSalt is to investigate how global warming will affect the biodiversity and greenhouse gas emissions of Nordic salt marshes. Since the establishment of larger experimental setups in nature is challenging, we decided to build a mesocosm experiment. A mesocosm is a controlled outdoor experiment, which is supposed to enable researchers to better understand complex natural interactions. You may say that a mesocosm lies in between the lab and the field.

The mesocosm will be established at Hamburg University. In NordSalt, we collected both grazed and ungrazed salt marsh blocks from Finland, Sweden and Denmark.

In Denmark, blocks were taken from a marsh at Mariager Fjord. One site was grazed with cattle, while the other site was unmanaged and covered by tall reeds.

Once the mesocosm is finalized, the blocks will be set in a saltwater tank as to mimic natural conditions in the field. We will simulate different climate change scenarios by warming the blocks with the respective expected temperature. After a short acclimatization period, we will be able to measure several vegetation traits and greenhouse gas emissions in each block. We look forward to seeing results, as it was hard labor to retrieve the blocks from the marshes! Thanks to our inventive German collaborators, we had specialized tools to cut out the exact needed size of blocks.

Digging and cutting to excavate the needed soil blocks for the mesocosm experiment. Early November, Denmark.

In total, more than 6 tons of marsh soil was transported to Germany. In Denmark, the heavy boxes were transported on a little trailer with an ATV. This is where field works becomes extra fun!

The heavy boxes filled with salt marsh blocks were transported on a trailer behind an ATV, which could easily access the difficult terrain.

The mesocosm experiment will allow us to measure warming effects on salt marsh soil that comes from areas that naturally differ in soil salinity, with grazing and without grazing management. We will observe the development of species diversity, plant traits such as leaf area or height, and gas emission in the form of methane and carbon dioxide, over several years throughout all the seasons. Such a comprehensive study would rarely be feasible in the field.

All pictures taken by Franziska Eller, except the last one, taken by Kitte Linding Gerlich.

Franziska Eller

Adjunct Professor, Department of Biology, Aquatic Biology

Aarhus University

NordSalt Blog Post #04 - November 2021

Biodiversity in Nordic saltmarshes and climate change; what are the links?

Grazed coastal meadows along the Baltic Sea coastline are well-known to harbor relatively diverse plant assemblages that include rare species that benefit from grazing and the unique, semi-wet environment. Together with the role of these habitats for breeding birds, the benefits for plant diversity is one of the main reasons why managers want to maintain this unique habitat type. But does it really matter whether these areas harbor a mixture of small, grazing-tolerant plant species or ‘just’ dense reed stands – and for what does it matter? These are some of the questions we’re addressing in the NordSalt project, and here we’ll explain why.

Picture 1: Reeds in a saltmarsh in Sweden; Picture 2: Potentilla Aserine, a common plant found in some salt marshes in Sweden (© Line Andersen)

Ecologists have over the last decades become increasingly aware of a couple of aspects when it comes to the functional role of biodiversity. First, biodiversity (for example, the number of plant species in a small field) typically has a positive effect on processes like plant biomass production, with clear benefits on ecosystem services like crop production. This can be explained by an overall more effective use of available resources and/or facilitation between co-occurring species that differ in some traits and thereby complement each other. Second, in changing environments (high) biodiversity can also act as an ‘insurance’, by increasing the likelihood that there will always be some species that is tolerant enough to uphold important processes when others fail. A similar reasoning is the basis for investing in a stock portfolio, rather than betting all savings on the company that does best at present. Third and finally, we see increasing evidence of strong linkages between climate change and biodiversity; diverse ecosystems can be more resistant to climate extremes and may be better at mediating (buffering) the impacts of greenhouse gas emissions. At the same time, however, climate change is already reducing biodiversity and homogenizing ecosystems (by favoring certain types of species while impacting many others), with knock-on effects on ecosystem processes.

Picture 3: Salt marsh reed bed in Finland (© Chris Böstrom); Picture 4: Plant life in Danish salt marsh (© Carmen Leiva)

The NordSalt project rests on a couple of hypotheses that link biodiversity of marsh plant communities with climate change, which we are testing using a combination of comparative field surveys and experiments over the coming years (Fig. 1). First, we hypothesize that both plant species composition and diversity (for example, the number of plant species) are strongly influenced by grazing and local environmental conditions like salinity. Second, plant composition and diversity may both influence how much carbon that is stored in plant biomass and soils, but also the uptake and release of greenhouse gases like carbon dioxide and methane. We also believe that more diverse plant communities stabilize the soil better, preventing soil erosion and loss of already stored carbon. Finally, climatic changes like warming and sea level rise should impact the plant community composition and diversity, with knock-on effects on the ‘blue carbon’ ecosystem processes. However, it’s also possible that grazing – by facilitating certain species – may mediate (buffer or exacerbate) the impacts of such climate impacts on ‘blue carbon’ services, with effects that would feedback on to the plant communities in the long term.

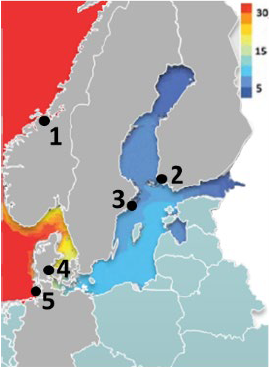

Fig. 1: Test sites for comparative studies in NordSalt; Picture 5: Carefully identifying different plant species in Sweden (© Line Andersen)

So what are we finding? Well, since this first field season has just been completed it’s too early to tell. But to give you a teaser, our preliminary findings from Sweden look very promising…! If you want to know more, make sure to check the NordSalt webpage regularly and to follow us on Twitter @NordSalt

Johan Eklöf

Associate Professor, Director of Studies in Marine Biology

Department of Ecology, Environment and Plant Sciences (DEEP), Stockholm University

NordSalt Blog Post #03 - September 2021

5 salt marsh ecosystem services in a nutshell!

Ecosystems services (ES) are benefits provided by natural ecosystems to society. These services can come in many forms, for example wood provided by forests or oxygen to breath provided by grasses. Salt marshes are known worldwide to provide important ES related to coastal protection, nutrient removal, and CO2 sequestration (so called Blue Carbon - BC). Salt marshes in the Nordic region are, however, different than salt marshes elsewhere in the world, both in terms of the plant communities and ecological dynamics. In the NordSalt project we are studying the BC storage, biodiversity, and ecological processes in grazed and ungrazed salt marshes and meadows in the Nordic region. Ultimately, we hope to quantify the ES provided by these habitats, based both on the ecological measurements made and inputs from diverse stakeholders. Work with stakeholders is facilitated by Rachel Tiller’s team at SINTEF, Norway. Below we describe some of the important ecosystem services provided by Nordic salt marshes:

1. (Blue) carbon sequestration is an important regulating salt marsh ES in that helps moderate CO2 levels in the atmosphere by taking up CO2 during plant photosynthesis and storing this C in biomass and ultimately in marsh soils. Thus, along with mangroves and seagrasses meadows, salt marsh can be an important tool for climate change mitigation.

Core sampling in a grazed salt marsh. Belowground carbon pools usually comprise most of the BC stocks in salt marshes. (© Jake Reardon)

2. Another regulating ES provided by salt marshes is coastal protection. Marshes, which grow on the land margin at the edge of the sea have the capacity to dampen waves and to “absorb” water from tides and storm surges. This provides so called “soft” protection for the coastline and flooding (in contrast to “hard” protection of seawalls or dikes).

Tall reed grasses can act as physical barrier dampening wave action and preventing soil erosion. (© Rachel Tiller)

3) Given their location at the edge of the sea, salt marshes are also important sites of water quality regulation through nutrient removal and retention. Marshes thus play an important role in filtering nutrients coming from the land (e.g., agricultural fields) to the sea. Such nutrient cycling, retention and removal is an important regulating ES.

Located in the interface between terrestrial and marine system, salt marshes can intercept terrestrial runoff of sediments and nutrients. (© Rachel Tiller and Jake Reardon)

4) Salt marshes are unique habitats and important supporters of biodiversity, a provisioning ES. For example, certain bird species prefer the high reed plants found in ungrazed marsh habitats. On the other hand, grazed salt marshes are known to have a higher plant diversity and thus provide habitats for a variety of insect species.

Insects, birds, small mammals and other animals benefit from diverse habitats provided by salt marshes. (© Rachel Tiller and Jake Reardon)

5) Salt marshes offer opportunities for recreational and educational activities, and inspiration for art and spiritual experiences. Such cultural ES include wildlife and birdwatching, walking, picnicking, among others. Therefore, salt marshes also provide non-material benefits that are essential for human health and well-being.

The beautiful sceneries offered by salt marshes for contemplation. (© Rachel Tiller)

In the NordSalt project, we plan to assess and quantify many of these important ES provided by Nordic salt marshes and in doing so increase awareness of the beneficial role these marsh ecosystems have for society. Stay tuned!

Gary Banta

Head of Department, Associate Professor

Department of Biology, University of Southern Denmark

Marianna Lanari

Postdoc researcher

Department of Biology, University of Southern Denmark

NordSalt Blog Post #02 - August 2021

5 things you need to know about sampling in nordic salt marshes!

One of the aims of the NordSalt project is to determine the carbon budgets in five representative Nordic marsh habitats. To do so, we need to go to the field and get samples that allow us to get information to answer these questions. There is generally a lot to consider and prepare before sampling in any ecosystem, and sampling in a saltmarsh is no exception. Here we list five of the most important things a scientist should remember when sampling in a salt marsh.

1. Always consult the weather forecast the day before.

This is especially important if you are sampling in a Nordic country. In the summer, weather can be a bit unpredictable, and you won’t have certainty sometimes even until the sampling day. Therefore, always be prepared and pack waterproof clothes. Do not forget either waterproof paper to not lose the precious field data under the rain.

2.Have a nice breakfast and take some snacks with you because you will need energy to hammer and retrieve the sediment cores!

In this project, one of the most important samples that we have to get from the saltmarsh is the sediment cores, which are not easy to obtain, especially if the soil is not wet enough. If that is the case, you’d better have a colleague to alternate with while getting the core because it can get quite exhausting!

3.If the weather is too windy, you will need good clipboard folders.

It may sound silly but a double clip clipboard can save you a fair amount of time in the field if the weather is windy. Otherwise, you will be frequently rearranging the data sheets and if there are gusts of winds, you could end up running after the data sheets to recover the valuable data that it took you a while to collect.

4.Do not forget to take a look at the tidal prediction in the nearest station.

Regarding the tides, this is key because we are working in the low salt marsh where the soil elevation is not high. Even if the amplitude of the tides in the Baltic sea is generally small, when various forces combine (spring tides) the amplitude can be as high as 40 cm. If that happens, your sampling point may get underwater, making the entire process very difficult.

5. Last but not least, bring insect repellent with you and wear covering clothes.