New collaboration on experimental particle physics

What is out there in the universe, and how can we describe it? These are questions that theoretical physics often seeks to answer. Now, University of Southern Denmark physicists are joining forces with Europe's second-largest particle physics laboratory, hoping to capture elementary particles.

The universe remains one of science's greatest mysteries, and we lack answers to fundamental questions such as: what is out there? We know less than 20 percent of the matter that exists in the universe – this is the matter that everything known – you, me, and the stars – is made of. The remaining more than 80 percent is unknown, and in the absence of a better term, we call it dark matter.

Although physicists do not know what dark matter is, they know it must exist. Otherwise, there would not be enough mass to hold the universe's structures of galaxies and galaxy clusters together (they are held together by the gravity from the mass of the structures).

– One can reasonably assume that dark matter could be some elementary particles that we do not yet know. Maybe because they do not behave like the particles we know and can measure and weigh, says Manuel Meyer, a physicist at Department of Physics, Chemistry and Pharmacy, University of Southern Denmark.

Meet the researcher

Manuel Meyer is a physicist and associate professor at the Department of Physics, Chemistry, and Pharmacy. His research is supported by a European Research Starting Grant of 11 million DKK

Theoretical physicists try to calculate the occurrence of such yet unknown elementary particles. However, there are also several large physics laboratories where physicists attempt to detect elementary particles through experiments.

This is done, for example, by accelerating known particles to an extremely high speed and letting them collide with each other to see what happens – whether they split into smaller elementary particles, which might be the long-sought dark matter.

In Hamburg, the physics laboratory Deutsches Elektronen-Synchrotron (DESY) is located. It is Europe's second-largest physics laboratory, and here, they also search for elementary particles.

What is an elementary particle?

An elementary particle is a particle that cannot be divided into smaller parts. Currently, we know about 24 (12 elementary particles, each having an antiparticle). Once, it was believed that the atom was the smallest elementary particle, but research has shown that the atom consists of even smaller elementary particles, and it is possible that scientists will discover even more. There are two types of elementary particles: matter particles (fermions) and force particles (bosons). The photon is a well-known boson, responsible for electromagnetic phenomena such as X-rays, ultraviolet light, visible light, microwaves, and radio waves.

The University of Southern Denmark has now made a collaboration agreement with DESY, primarily focusing on the hunt for the presumed – but not yet proven – elementary particle, the axion.

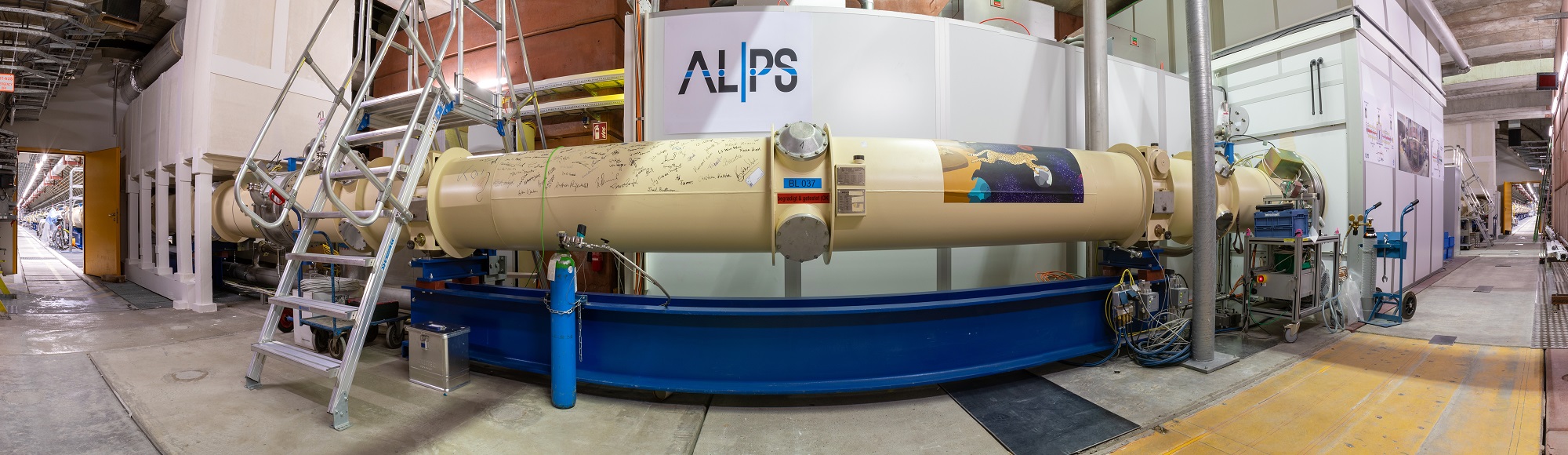

Physicist Manuel Meyer, is interested in the axion and is preparing major experiments where he and colleagues will attempt to detect an axion in DESY's facilities. This experiment is called Any Light Particle Search (ALPS II).

Lars Porskjær Christensen, head of the Department of Physics, Chemistry and Pharmacy, is not only delighted on behalf of the researchers but also for the students regarding the new collaboration with DESY:

– DESY is located in Hamburg, and it's only three hours by train from our campus in Odense. It opens up exciting opportunities for our students to participate directly in groundbreaking particle physics experiments while studying at SDU, he says.

About the collaboration

SDU hosts the collaboration with DESY through the Center for Cosmology and Particle Physics (CP3 Origins), which includes researchers from both the Department of Physics, Chemistry, and Pharmacy and the Department of Mathematics and Computer Science. The group works on fundamental particle theories, computer simulations of these as well as cosmology.