Frodo the humpback whale goes on an adventure

A new study confirms that humpback whales most often return to the same breeding and feeding grounds on their annual migrations through the world's oceans. But then there is Frodo; he did not swim back to the same place but ended up 11,261 km away.

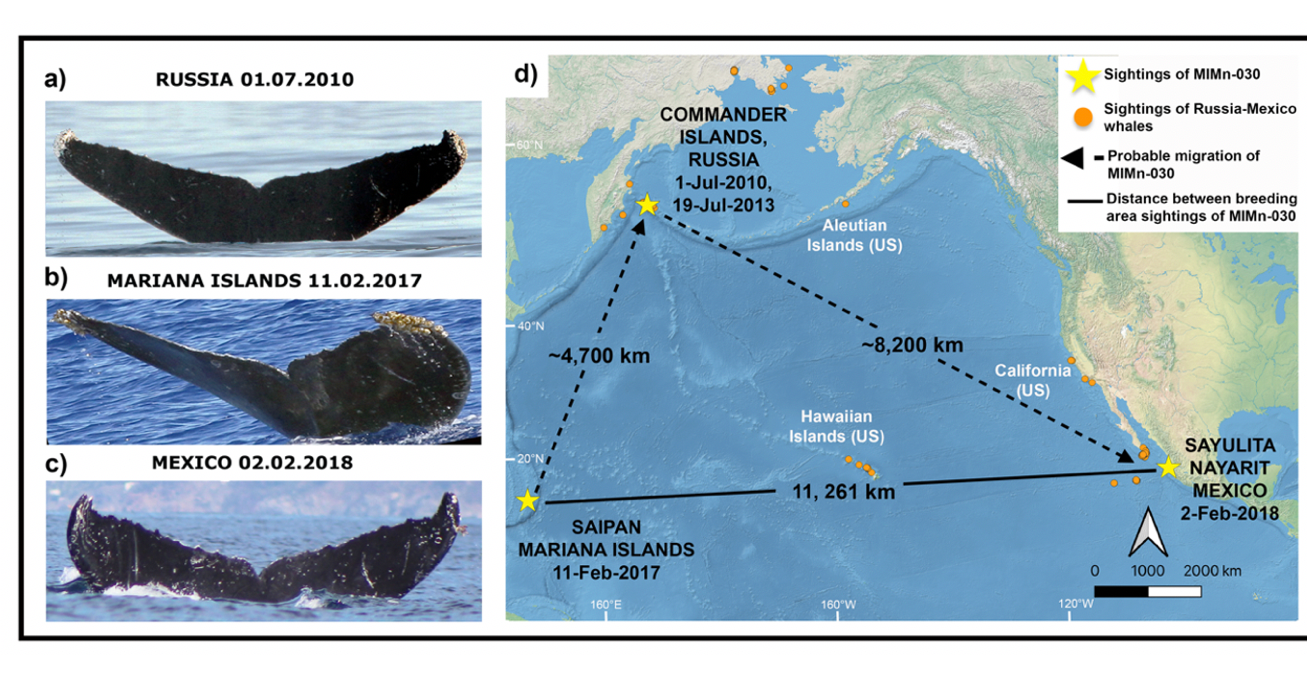

On 17 February 2017, the humpback whale Frodo was spotted off the island of Saipan, south of the Philippines. 357 days later he appeared off Mexico. The fact that he got so far away has surprised biologist and whale expert Olga Filatova from the Department of Biology.

– The humpback whales that live off Saipan in the winter usually return to Saipan after they have been north for the summer to feed. But then Frodo didn't. We don't know why. Maybe he joined another group and swam with them to Mexico instead, she says.

The observations of Frodo and other humpback whales are the basis for a new research paper published in the journal Endangered Species Research, authored by Olga Filatova and colleagues from Australia, Mexico, Russia, Honolulu and the USA. First author is Nico Ransome from Murdoch University, Australia. You can dive into their article here.

Humpback whales

There are approx. 112,000 humpback whales living almost all over the world, and they are divided into 14 groups. They are ca. 16 meters and weigh ca. 30 tons. They live on krill and fish that they catch in the summer. In winter, when the females also give birth and nurse their calves, they do not eat anything. Commercial whaling for humpbacks has been prohibited since 1966.

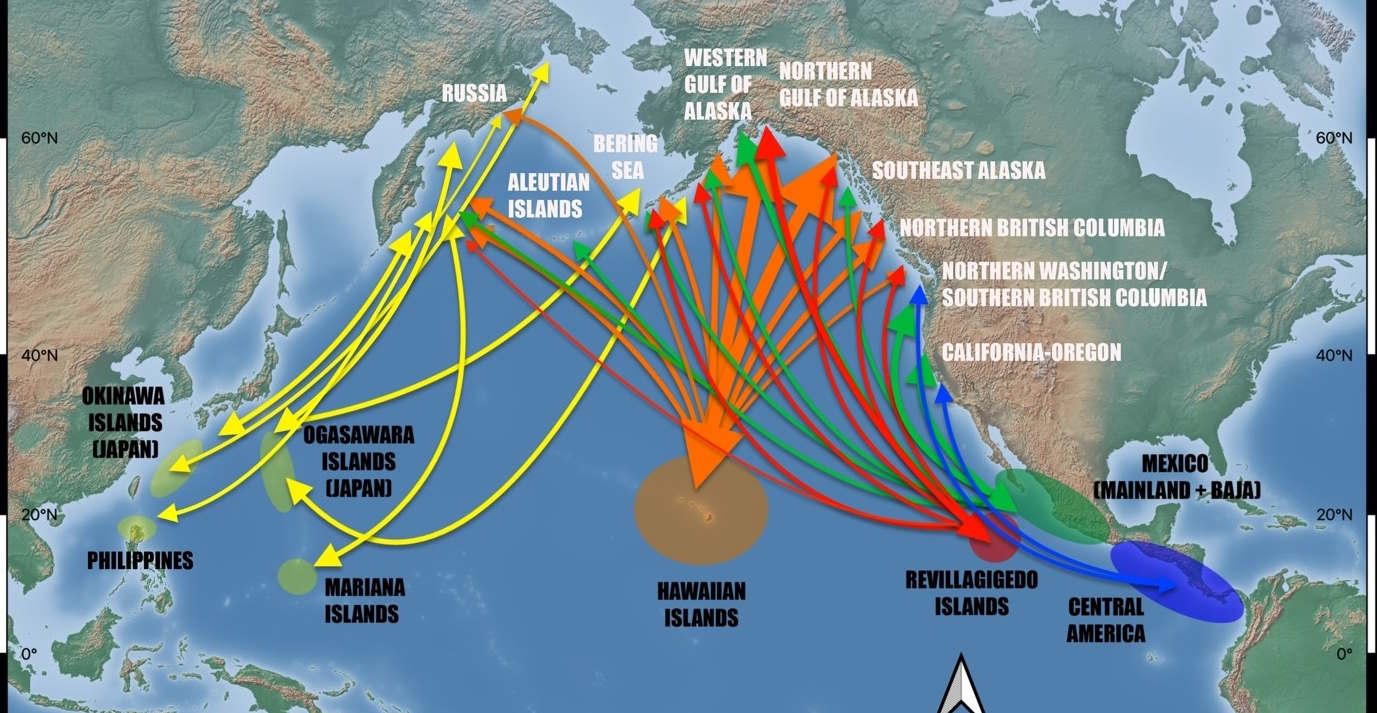

The study has analyzed 18,852 observations of humpback whales in the North Pacific, and it reveals regular migrations of humpback whales between Mexico and Russia.

– We know that once a calf has been to a certain breeding and feeding ground with its mother, it will normally return to the same spot for the rest of its life. We see the regular migration between Mexico and Russia as an expression for that, says Olga Filatova, adding:

– Unless something serious happens, such as their food disappearing from their usual feeding grounds, they will go to the same places.

Threats on the high seas

Although the high seas are desolate, there are still threats to the humpback whales. They risk being entangled in fishing nets or struck by passing ships that don’t see them in time.

All humpback whales in the North Pacific travel several thousand km per year as they migrate from southern, warm waters to cold, northern waters and back. In the winter they stay in the south, for example near Mexico, Saipan and Hawaii, to mate and give birth to their calves, and in the summer they swim north with their newborns to find food. Examples of northern feeding grounds are Alaska, the Bering Strait and the Commander Islands off Kamchatka on the Russian coast of the North Pacific.

Some of the study's animals cover what appears to be unnecessarily long distances. This applies especially to the groups that live off Mexico in the winter and swim up to the Commander Islands in the summer; a stretch of 8,200 km as the crow flies.

– One can wonder why they don't just go to Alaska, which is only 4-5,000 km from Mexico. There is plenty of food for them off Alaska. But they don't - and that illustrates how strong traditions are among humpback whales, says Olga Filatova.

Frodo has also been north in search for food. He has previously, in 2010 and 2013, been spotted at the Commander Islands, so it is not unlikely that he went there between his winter stays Saipan and Mexico. If so, in one year he has traveled 4,700 km from Saipan to the Commander Islands and 8,200 km from the Commander Islands to Mexico, a total of 12,900 km.

What is special about the feeding grounds at the Commander Islands is that they attract many different groups from different origins, and perhaps Frodo joined one of these groups.

The many observations that form the basis of the researchers' scientific article come from the citizen science and research project happywhale.com, where everyone, from researchers to tourists, can upload photos of humpback whales' tail fins.

The tail flukes of all humpback whales are different and can be used to identify individual animals. On happywhale.com, artificial intelligence looks for matches between uploaded photos – just as we use technology for facial recognition in humans. Thus, the system provides researchers with information about where and when individuals have been seen and photographed. The system has so far identified 102,064 individual humpback whales.

Meet the researcher

Olga Filatova is an expert in whales and a postdoc at the Department of Biology. She is also associated with the SDU Climate Cluster.