Why is there still a chip shortage?

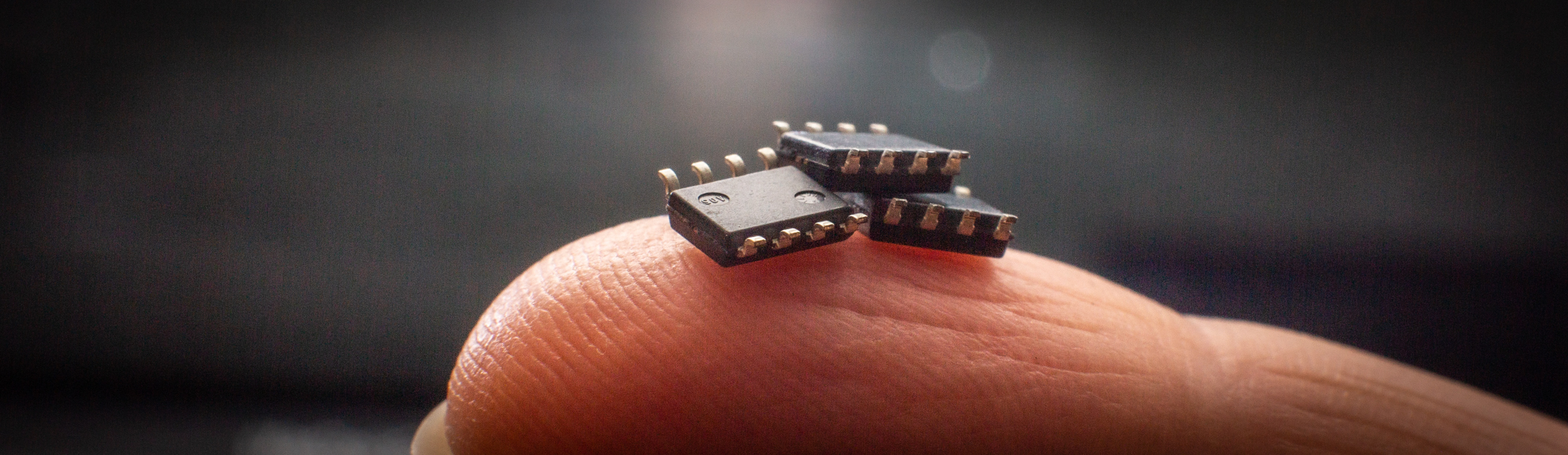

Microchips are rather small - but have huge importance in a digital international community. It was felt clearly during 2021, when consumers experienced popular products as cars, mobile phones and game consoles were in short supply. But why is there still a chip shortage? SDU-expert Tim Van Erp explains the situation.

Why are the chips missing?

Basically, the global semiconductor chip production lacks manufacturing capacities for fulfilling the increasing global demand. The Covid-19 pandemic led to a shutdown of global production facilities and thus to decreasing global inventory of semiconductor chips. On the flip side, we can see an increase in demand for these chips due to current trends towards electrification and digitalization across all industries. As a result, more and more companies compete for limited capacities provided by the existing semiconductor foundries.

Can you name some examples?

In the financial industry for example, cryptocurrency mining has recently led to a demand surge for graphic cards, but the graphic card manufacturers are competing for the highly scarce capacities from their contract semiconductor manufacturers. The result: low availability and skyrocketing prices for graphic cards. We can currently also see that the low availability of chips led to some companies stockpiling and buying beyond their actual demand which in turn even adds more pressure to the global supply chains. On top of that, increasing extreme weather events, a fire in a Japanese plant, and disruptions and delays in global transportation chains post Covid-19 do not help resolving the situation – rather the contrary. More volatile global supply chains have added to the problem of chip shortage, though it is not the main obstacle in the current situation.

Why can’t we get them somewhere else?

While the global semiconductor market grew substantially during the last decades, Europe’s share on the global semiconductor production has significantly decreased. The semiconductor industry is now dominated by a few global players located mostly overseas. For example, Taiwan is home to the two largest contract manufacturers in the world. The companies just have no choice, they are dependent on the few semiconductor foundries which are already operating on full capacity.

Why can’t we just increase the production capacities then?

The design and production of semiconductor wafers is a rather complex process. For example, the technology development and chip design can take up to three years and the wafer production can easily take four months from start to delivery. Hence, capacity building requires know-how, high investments and fairly long time periods. The investments made today in new foundries will only add real capacities in a couple of years.

What effect does this have on different branches?

We are currently seeing that digitalization and electrification are among the global trends effecting most branches. This means that manufacturing companies in general tend to integrate and embed more and more electro components, such as sensors, actuators, controllers, or processors, into their products and in with this also semiconductor chips. The impact of the chip shortage is especially seen across the electro industry’s lead markets: building, energy, mobility, health, and Industry 4.0. For example, the expansion of electromobility and renewable energy sources are highly dependent on a sufficient chip supply. Many manufactures in these sectors currently cannot meet their delivery deadlines or are even stopping their production due to missing electronic components. Tesla, for instance, as a consequence have delivered cars without USB-connector to their customers.

Who is trying to solve it – what will it take to solve the problem?

The semiconductor manufacturers have already started building up the capacities of their foundries, but the shortage might be lasting until 2023 according to some forecasts. However, the chip shortage appears to also have led to a rethinking of the Industrial Strategy of the European Union. “Technological Sovereignty” seems to be one of the new buzz words you can hear more and more often in Brussels. This also means that the European Commission intends to bring back chip manufacturing competences to Europe. For this reason, the Commission just recently launched a so-called “Important Project of Common European Interest“ together with 32 companies and research and technology organizations from four EU member states for strengthening the European microelectronics industry. We will see on the long run if these activities will have a significant impact on our European competences and capacities throughout the semiconductor and microelectronics industry or if we remain mainly dependent from American and Asian suppliers. Yet, there seems to be no short-term solution to the chip shortage.

Meet the reseacher

Tim Van Erp is an assistant professor at the Department of Technology and Innovation at SDU. He researches – among other things – electrical industry and sustainability.