How do we support those unable to conceive naturally?

Professor Jens Fedder, with 40 years of research experience in fertility treatments, offers insights into the evolution and history of these treatments, as well as prospects and opportunities.

As early as 1790, surgeon John Hunter successfully fertilised a woman using her husband's sperm, leading to the birth of a child. This instance represents the earliest documented case of artificial insemination. Today, 15% of all couples in Denmark experience reduced fertility at some stage and therefore need assistance to conceive.

Professor Jens Fedder, from the Department of Clinical Research, is a leading expert in assisting couples who are involuntarily childless. With 40 years of research in fertility under his belt, we asked him about the current state of fertility treatments in Denmark.

-Fertility treatment has advanced steadily since the first controlled inseminations using sperm in the 1940s. The most significant milestones would certainly include IVF treatment, and microinsemination, explains Jens Fedder.

IVF Treatment and Microinsemination

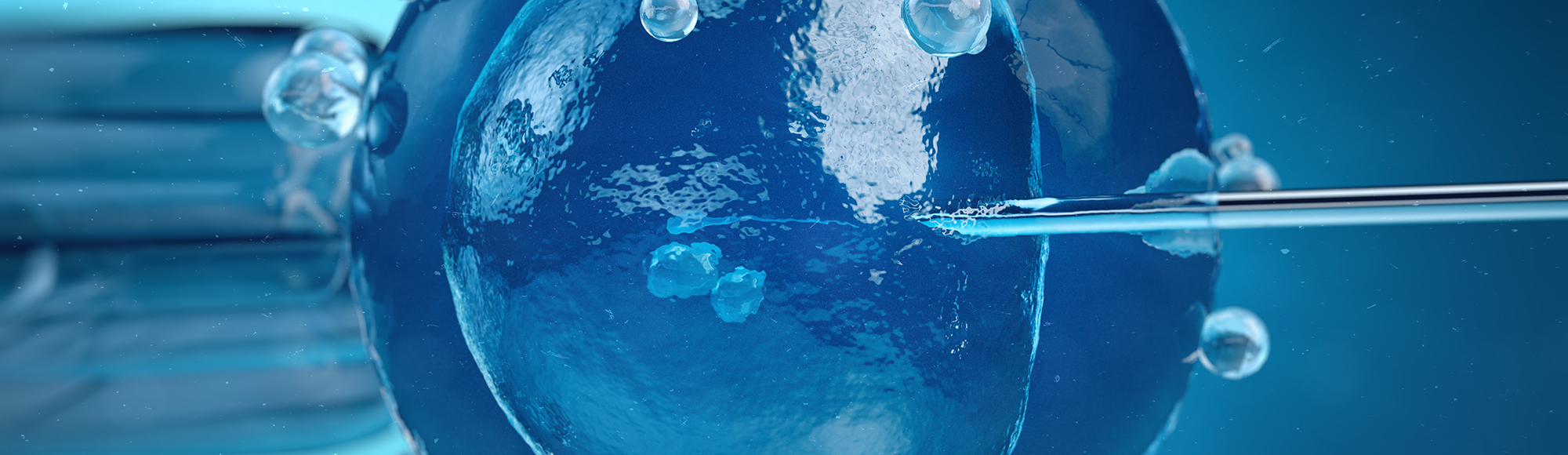

IVF stands for "In vitro fertilisation," derived from the Latin phrase "in vitro," meaning "in glass." This procedure entails fertilising a woman's egg with a man's sperm outside the body in a laboratory setting. Around 100,000 sperm cells are introduced to each egg, with the most viable sperm cell achieving fertilisation.

Once the egg is fertilised, it is returned to the woman's uterus. There, depending on several factors including the woman's age, it develops into a fetus in 40-50% of cases.

In microinsemination, sperm cells are purified and the optimal one is selected to fertilise the woman's egg. This process involves isolating a single egg and directly injecting a single sperm cell into it using a needle.

- Microinsemination is employed for couples where the man has significantly reduced sperm quality. This enables men, who otherwise would not have the opportunity, to become biological fathers, explains Jens Fedder.

Your Skin Cells Could Potentially Become Sperm Cells

In Jens Fedder's laboratory at Odense University Hospital, he and his research team have dedicated many years to maturing sperm cells in the lab. This process involves using precursors to sperm cells—referred to as stem cells—and exploring their potential to develop into healthy sperm cells.

-In the initial experiments, we utilised what are known as embryonic stem cells, which are found in the fertilised egg. These stem cells are located where the fetus develops, explains Jens Fedder.

The plan for the next phase involves deriving stem cells from skin biopsies. These are the so-called pluripotent stem cells, with which Jens Fedder and his colleagues intend to work. Pluripotent stem cells have the capability to develop into any cell type in the body, depending on the signals they receive.

Pluripotent Stem Cells

The term "pluripotent" derives from Latin, where "pluri" means "several" and "potent" means "powerful." Combined, these elements describe something with the potential to assume various forms. A "pluripotent stem cell" refers to a stem cell's capacity to develop into almost any cell type in the body.

The development of the stem cell is influenced by signaling molecules, such as the body's hormones, and the surrounding environment, or the specific location of the cell.

As the stem cell matures, it becomes increasingly specialised; for instance, it can differentiate into a sperm cell.

-Our research holds the potential to assist men who otherwise lack sperm production in their testicles to become biological parents, explains Jens Fedder.

Thus far, researchers have successfully induced embryonic stem cells from mice and rats to develop into mature sperm cells. However, this process proves more complex in humans, with significant progress yet to be made in developing human stem cells.

The sperm quality among Danish men has been on the decline, but this trend seems to have stabilized in the past 5-7 years. Genetics may partially explain this decrease in sperm quality.

Genetics and Diseases

-Genetics play a crucial role in determining sperm quality. Currently, researchers around the globe are identifying a new gene approximately every two weeks that impacts male fertility, explains Jens Fedder.

Jens Fedder and the Fertility Clinic collaborate with departments of molecular medicine and clinical genetics in Denmark on fertility and genetics issues. Jens Fedder notes that while they cannot test for all possible genetic anomalies, they possess a profound understanding of certain genetic alterations. For instance, they are knowledgeable about the genetic changes that cause Klinefelter's syndrome, a condition where a man has an extra X chromosome.

Klinefelter's Syndrome is not only easy to test for but also so common that it justifies routine screening. Additionally, other genetic disorders besides Klinefelter's Syndrome can adversely affect fertility.

Some genetic alterations, for instance, can cause blockages in the sperm ducts. In such cases, it is feasible to assist the man by extracting sperm cells through a minor needle biopsy and fertilizing the egg via insemination. Additionally, other genetic changes that reduce sperm count may be addressed with microsurgery as a potential solution.

Microsurgery

Microsurgery, also referred to as micro-TESE, is employed when sperm cells cannot be retrieved through a standard needle biopsy. This technique is particularly useful when sperm production is limited to very small, localised areas within the testicles.

Today, more women with chronic diseases are receiving assistance in becoming pregnant than in the past. This increase is due partly to the rising number of women diagnosed with chronic conditions and partly to advancements in the available fertility treatments.

- Even though there is a marginally reduced chance with some of these chronic conditions, we are able to assist women with diseases such as arthritis and diabetes, explains Jens Fedder.

What can aid these women is highly individualised, for instance, in terms of adjusting their medication. Jens Fedder emphasises the need for more research into fertility treatments for women with chronic diseases to provide more precise assistance to each individual.

Uterine Transplantation: A Viable Option

Uterine transplantation offers another avenue to assist couples without children. Since 2014, Sweden has successfully performed uterine transplants. Generally, women who have finished having their own children donate their uterus to others who need it, such as women who have undergone a hysterectomy due to cancer treatments.

- It is indeed possible, and healthy children are being born. However, the transplanted uterus must be removed once the desired number of children have been born. This is necessary to avoid prolonged use of immunosuppressive therapy, which would be required as long as the transplanted uterus remains, explains Jens Fedder.

The Danish Council of Ethics has so far rejected this treatment. However, Jens Fedder notes that it is a topic that is frequently revisited, similarly to discussions about the use of surrogate mothers.

The Future of Fertility Treatment

Researchers are continually advancing established fertility treatments, such as IVF and microinsemination, to offer optimal support to individuals facing involuntary childlessness.

Jens Fedder suggests that future developments in fertility treatment will focus on understanding the reasons behind the decline in sperm quality among men.

- Although we are achieving technological advances in treating male infertility, we must persist in our efforts to comprehend why human sperm quality is deteriorating. Research indicates that environmental factors and modern lifestyles might be contributing to this decline, but these relationships need more detailed investigation and mapping, he explains.

Meet the researcher

Professor Jens Fedder, Research unit of Gynaecology and Obstetrics (Odense), Department of Clinical Research, University of Southern Denmark, and Center for Andrology and Fertility, Odense University Hospital. Jens Fedder has 40 years of research experience in fertility treatments.