Danish King got enshrined in his own clothes – but appeared with his brothers’

Scientific analysis solve puzzle about the age and destiny of precious silk textiles from AD 1100.

The cathedral in Odense, Denmark, has for nine centuries held the relics of the Danish King St. Canute the Holy and his brother Benedikt. They were both murdered here in AD 1086, and just a few years later, in AD 1100, King Canute was sanctified.

The history of the relics has been that of turmoil at times, varying from initial worship of the Catholic believers to being walled up and hidden after the protestant reformation in AD 1536.

Since the 19th century the brothers’ wooden shrines have been on display in the cathedral as heritage objects of national importance.

How old are the silks?

The shrines of Canute and Benedikt have long been a puzzle in Danish history. They both contain several well-preserved textiles of silk and linen and the question is: How old are the textiles and what is their historical context?

Now, researchers have examined some of the textiles in the two shrines. They conclude that King Canute’s shrine no longer holds the precious silk textiles placed in it at his enshrinement.

Instead it is likely that the textiles from his brother’s shrine at some point have been moved to King Canute’s shrine.

Were the king’s silks stolen?

According to historical sources, both brothers were covered in valuable textiles when enshrined. Sources have described how Canute’s shrine in AD 1536 was lined with beautiful and rare silk.

Decades later, both shrines were walled up in the cathedral, placed vertically so that the bones and textiles lay in a heap at the bottom of each shrine, and hereafter there are no reportings of the precious textiles in King Canute’s shrine when it was re-examined in AD 1694 and AD 1833.

– It is tempting to suggest that the king’s precious textiles have been stolen at some point after AD 1582, says professor and an expert in archaeometry, Kaare Lund Rasmussen from University of Southern Denmark.

”They are exquisite and beautiful, but King Canute’s textiles must have been even more exquisite.

When the two shrines were removed from their walled up hiding places and prepared to be put on display in 1874, researchers at the time were puzzled by the absence of valuable textiles in King Canute’s shrine - his brother Benedikt had the more valuable textiles – and they declared themselves unable to judge in which of the shrines the found fabrics belonged.

They decided to move the best textiles from Benedikt’s shrine to King Canute’s shrine, so that he could be presented with the most beautiful, most precious textiles when on display under a glass lid.

Professor Kaare Lund Rasmussen and colleagues have performed chemical analysis of the textiles in both shrines and conclude that they are of the same age, and that their age fit with AD 1086, when the two brothers were enshrined.

Birds and eagle motive

– Put together with historical sources this convinces us that today, King Canute lies in his shrine with what is actually his brother’s burial textiles, says professor Kaare Lund Rasmussen.

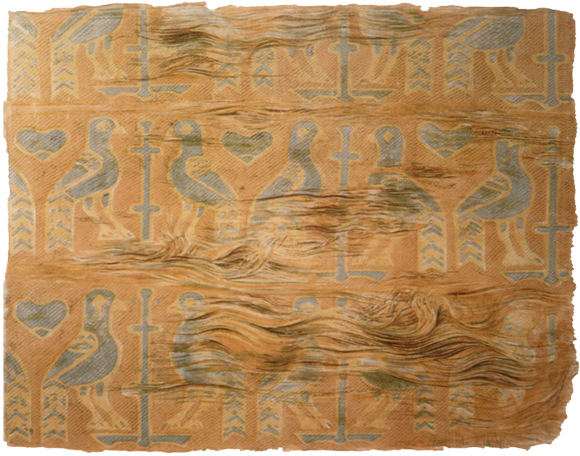

Among the textiles, intended for Benedikt but later placed with Canute, are a pillow with birds and a textile called the Eagle Silk.

– They are exquisite and beautiful, but King Canute’s textiles must have been even more exquisite, says Kaare Lund Rasmussen.

Illustration of St. Canute the Holy in top photo: Albert Haelwegh, SMK Open.

Precious silk

According to senior researchers at the Danish National Museum, Ulla Kjær and Poul Grinder-Hansen, the luxurious silks may have been sent from South Italy to the shrines in Denmark by King Canute’s widow, Edel, possibly brought home by Canute’s half-brother, King Erik 1. Ejegod.

At the time of Canute’s canonization and enshrinement, silk weaving in Europe was not yet established outside the boundaries of the Byzantine Empire and silk was both a precious and much-coveted import article.

Meet the researcher

Kaare Lund Rasmussen is professor of chemistry and a specialist in archaeometry: Using scientific techniques to analyze cultural heritage objects. He has previously analyzed the beard of Renaissance astronomer Tycho Brahe, the Dead Sea Scrolls and various sacred relics.

Contributors

The study is published in the journal Heritage Science. Other Danish contributors to the scientific paper are Ulla Kjær and Poul Grinder-Hansen, senior researchers at the Danish National Museum, and conservator Morten Ryhl Svendsen from the Royal School of Conservation in Copenhagen.